For many years, food brands have famously used stereotypical images of people of colour to promote products. Why is it essential for brands to rethink racist mascots? Max Ngari, Executive Creative Director at Isobar Kenya, decided to find out

The year 2020 will be remembered for many things, one of which is a collective global effort to end racial discrimination with one powerful movement: #BlackLivesMatter. However, when it comes to brands leading the charge in driving the change we all want to see, it has been a case of a little too much, too late. Seemingly, some brands have shifted from being forces for change to practitioners of faux activism, with many of these brands suffering the unfortunate fate of coming off as tone-deaf in their response. Taking the proverbial knee was just not going to cut it.

Like the butterfly effect, small things end up making a huge impact, and a movement that started with a march for life has subsequently unlocked a series of events that have led to widespread social awakening in every fabric of our lives. We are only beginning to fully understand the extent to which society has force-fed stereotypes of Black people.

Hiding in plain sight are brand mascots that openly discriminated against entire race groups and exploited Black and indigenous people for profit. It’s hard to imagine that some have been around for decades, but these colourful characters have been around so long and are so firmly entrenched in mainstream culture that nobody even registers them – and that is part of the problem.

Here are a few examples:

Aunt Jemima (Quaker Oats)

Aunt Jemima creator Charles Rutt came up with the name in the 1800s after seeing a minstrel show, which featured a “Mammy” called Jemima. Mammy is a Black maid, who proudly appears on pancake and waffle mix, and syrup packaging. She is presented as someone who is happily in servitude to her White masters. But after 131 years, Quaker Oats, the company that owns the products, is retiring Mammy, as the brand clearly perpetuates a racial stereotype.

Other controversial US brands

Aunt Jemima had barely come out with their plans when Mars announced Uncle Ben’s, their brand, would be following suit. Hot on their heels were B&G Foods, owner of Mrs. Butterworth’s, and Conagra Brands, which owns Cream of Wheat, both of whom say they will be reviewing their brands’ packaging. In an interview with USA Today, David Pilgrim, the director and founder of the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia in Michigan, in the United States, said that all these brands share one common element: that Black people are the happy servants of White people. ‘When we reduce people to that one dimension, it both shapes and reflects attitudes that people have about Black people.’

Clean & Clear: Clear Fairness (Johnson & Johnson)

Johnson & Johnson recently announced that it would stop selling its skin-whitening Clean & Clear: Clear Fairness line of products in India, as well as its Neutrogena Fine Fairness line, which is available in Asia and the Middle East.

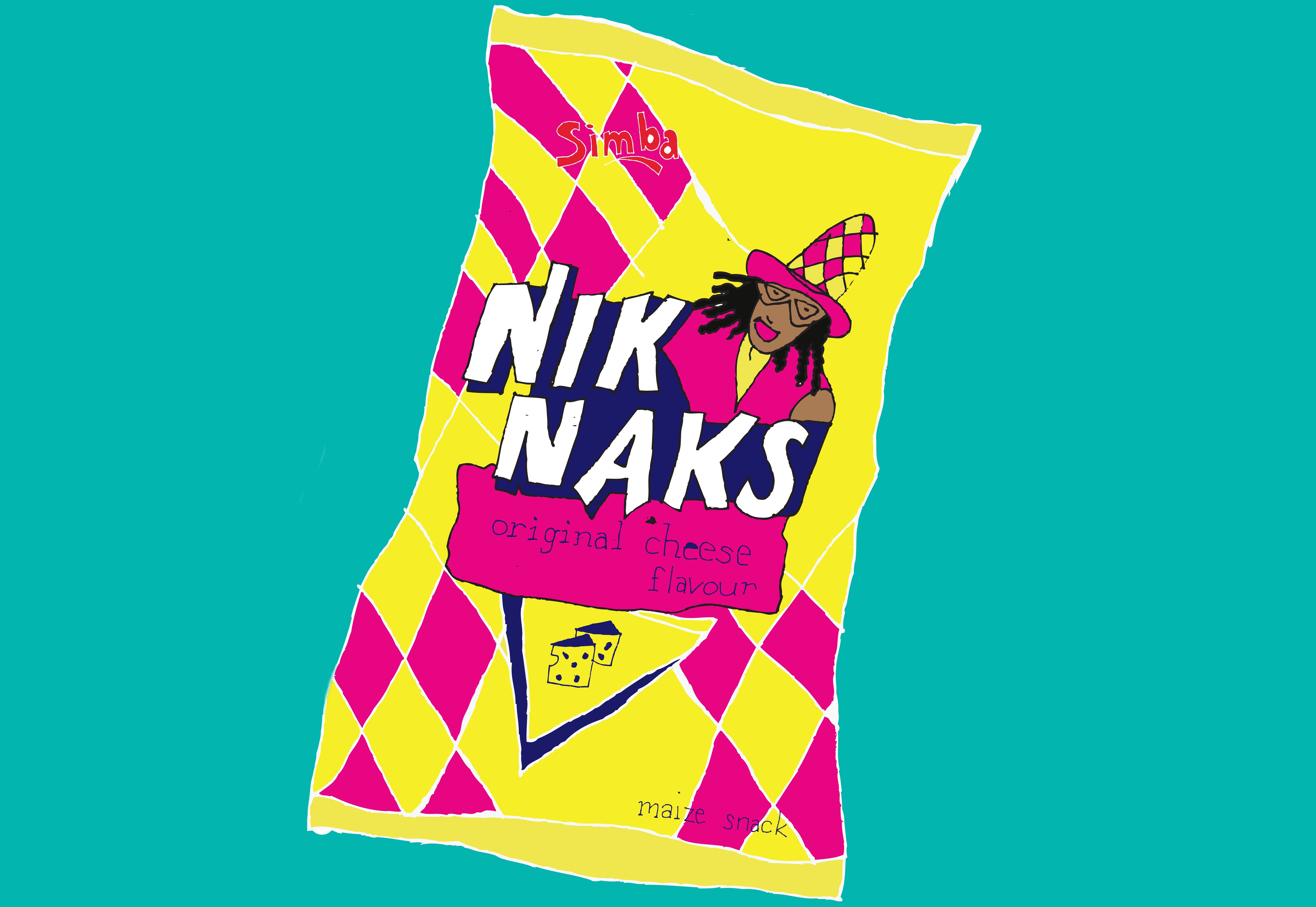

Niknaks (Simba)

Closer to home, in the early 2000s, Simba replaced the brand mascot Nik the Nak because he was a racial stereotype. The figure seemed to have been modelled to resemble a Kaapse Klopse minstrel with unnaturally large lips painted with white lipstick. He was replaced by a less prejudicial character, designed by Mzwandile Buthelezi and voted for by the public. Given the current debate, Simba should be acknowledged for a forward-thinking move.

Socially conscious brands look at what their brand stands for in today’s society – and tomorrow’s. They feed the change, digest it and, hopefully, learn and grow from it. This means looking beyond how Black people are depicted and focusing instead on how they are represented. This is ‘woke-vertising’ and it means understanding (certain aspects of) human history, analysing social and political structures and finding your own way to add your voice through knowledge.

Nike was one of the first proponents of woke advertising. They supported NFL superstar Colin Kaepernick in his stance on racial inequality in America. As Scott Galloway put it in response, endorsing the Muhammad Ali of this generation was a gangster marketing move. Surely it does pay to be on the right side of history?

---------------------------

About Max Ngari

Max Ngari comes from Nairobi, the capital of Kenya. He brings with him over 10 years’ experience in the creative industry, having worked as a creative lead at large and multinational brands in the telco, FMCG, software, financial services, business solutions and mobile technology spaces, just to name a few. His career has seen him work in many markets in Africa and Europe, expanding his exposure and strengthening the potency with which he develops creative solutions.